- COVER ARTIST -

LINDA MacDONALD

I

teach full-time at San Hedrin High School, a continuation high school

in Willits that has about sixty students. I've been there since 1985.

The classes are small so you really get to know the kids. Four of us teach

the whole curriculum. We have a little more flexibility than the regular

high school, and we give credit but not grades. I teach English, U.S.

history, art, textiles and a health class.

I

teach full-time at San Hedrin High School, a continuation high school

in Willits that has about sixty students. I've been there since 1985.

The classes are small so you really get to know the kids. Four of us teach

the whole curriculum. We have a little more flexibility than the regular

high school, and we give credit but not grades. I teach English, U.S.

history, art, textiles and a health class.

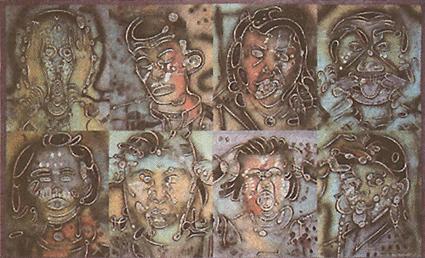

I talk to my students about my life because I want to show them that I have a life outside of school. If I go to a quilt show or teach in the quilt world, I always bring back something so they can see what I've been doing. They wanted to be in a quilt because they knew it might get into a book or a show and they could be part of it. So I made a quilt called "Faces around San Hedrin High School."

These kids are filled with personality. I had them make weird faces for me and I took photographs. I looked at the photos and airbrushed faces onto the rectangles of fabric, then dyed them in big washes of light pastels. Then I looked at the photos again, and painted in details with black and white paint. This is a cartoon technique. I like to have fun with images by using layers of patterning. Applying grids, I airbrushed patterns into these pieces and then painted them. They are not extremely realistic, but you can tell who the people are if you know them. I like that suggestion of who it is. My students have changed my artwork. I think of my job as a resource for my art.

My husband Bob and I bought land in Mendocino County in 1970 and moved here in 1971. I was a painter, but I also did weaving and textiles and had a big connection to fiber. Weaving didn't fulfill me totally because I wanted a more flexible medium for images. In 1973, I joined a consciousness-raising women's group in Willits, and the thirty or so women who came formed small interest groups. I participated in the drawing group and also in one that made a funky crazy quilt. After we finished, we drew straws and I won the quilt. I learned the basics of making quilts from a library book by Michael James. That was the only training I had. It's not that difficult.

My early quilts were repeat patterns of my own design made for the bed, but they were unusual. In the '70s, everything I saw was traditional. I had seen quilts done by female family members, and I liked the American folk-craft connection. Since we were living in the country, quilting seemed like a normal thing to do. By the '80s I had decided this would be my art form. If I had been living anywhere else, I don't know if this would have happened.

I have enjoyed staying with this medium, even though I do oil paint a bit and make some finished drawings. When I started showing in the early '80s, there was a wellspring of contemporary quilt shows. Not many people were focusing on contemporary designs then, so the same people were in all the national shows. I was always included, and I got a reputation right away. I was in the right place at the right time.

The quilts I became known for in the '80s were geometric landscapes. I developed this style on my own. I didn't know anyone who had done anything like this, and since I enjoyed doing them, they kept developing. These quilts take a really long time. Since many quiltmakers couldn't figure out my technique, periodically I'd go to summer symposiums and teach. There is no limit to what you can do, even if it is a challenge.

Eventually I got tired of the geometrics, and decided to do something

more personal that brought me closer to the fabric. Working at San Hedrin

High School, I figured out how to use an airbrush and I incorporated

that technique into my work. In making a quilt called "Amphora," I crumpled

the fabric, then airbrushed and ironed it. This created a three-dimensional

effect that was different from using perspective and standard principles

of three dimensional design. I had put a piece of fabric over my daughter

and tried to airbrush her figure into it, but it didn't look like a

human body, so I cut the fabric up and began experimenting, doing different

things with each strip. One strip contains what I call a "graffiti painting"

using airbrush and paint. The bottom was pointed, and I thought it went

with the head at the top. I called the quilt "Amphora," (see cover)

the name for an urn or vase used to carry water. It has a pointed bottom

that can fit in the sand, or it can be carried on the side of a horse

or camel. The quilt reminded me of that shape.

Eventually I got tired of the geometrics, and decided to do something

more personal that brought me closer to the fabric. Working at San Hedrin

High School, I figured out how to use an airbrush and I incorporated

that technique into my work. In making a quilt called "Amphora," I crumpled

the fabric, then airbrushed and ironed it. This created a three-dimensional

effect that was different from using perspective and standard principles

of three dimensional design. I had put a piece of fabric over my daughter

and tried to airbrush her figure into it, but it didn't look like a

human body, so I cut the fabric up and began experimenting, doing different

things with each strip. One strip contains what I call a "graffiti painting"

using airbrush and paint. The bottom was pointed, and I thought it went

with the head at the top. I called the quilt "Amphora," (see cover)

the name for an urn or vase used to carry water. It has a pointed bottom

that can fit in the sand, or it can be carried on the side of a horse

or camel. The quilt reminded me of that shape.

The process I followed was trance-like. It included airbrush, painting, italics, big thread, textures, and knots with threads hanging out. Pattern has always been thrilling to me. The patterns I see in what I create take me to other images, and I go from there. This spontaneous, emotional discovery process is unplanned and off-the-cuff. I am fascinated by how you can build up emotion through pattern. "Amphora" uses many types of pattern--dense in one area, more empty in others. I worked on it until it felt unified.

I dropped out of San Francisco State University in 1969 during the riots. I only needed twelve units to graduate, but I didn't go back until 1977, when I was living up here in Mendocino County and my daughter was about five. I knew I needed a normal kind of job, so thought I should finish my B.A. to become more hirable. I finished my units at Sonoma State by taking art classes and was able to apply the credits to San Francisco State. I got my B.A. in art from them in 1978.

I felt isolated from the art world living in Mendocino County, and I eventually decided I wanted to get a Masters in Art using quilts as a medium. I didn't know of anyone who had done that. I went back to San Francisco State, the only graduate school around here with a textile department.

In their three-year program, the graduate students in art took the same courses, whether they were painters, sculptors, ceramicists, conceptual design or textile artists. Distinctions are disappearing. Artists are saying "Why define yourself by your medium? What we need to do is artwork. Use whatever medium you want to use." There were interesting power struggles going on--the conceptual design people thought the printmakers were an anachronism; the textile artists were usually all women (some people wondered why this was still the case); and the painters were saying, "Look painting isn't dead, we're still here." I had a really good time. It was a pleasure to do my work and have people respond to it. I completed three years of study, wrote a thesis, did a show and graduated in 1992. It was pretty intense, but my family was very supportive and things worked out. At that time, I had a twelve-year-old son and my daughter was nineteen.

My early work was concerned with good design and color, three-dimensional impact and technique. I wasn't telling a story or making a political statement. I became more political and idea-oriented in graduate school. I was sort of forced into that because people are always asking us what we were doing. I felt different from the people in San Francisco. I had been living outside the Bay Area for twenty years. I often had to drive three hours in the rain to get to school. I thought my work should be more specific to my locale. My graduate show was coming up the next year, and I needed a series of works that made a statement and tied together. That was the time of the "Redwood Summer" in Mendocino County; I decided then to do the "spotted owl vs. the chain saw" series.

The "Wild and Tasty" piece came first. The spotted owl is canned and the can is based on a tuna can. The owl is a ghost with chain saws attacking it from all sides. It's really pretty corny. The owl on the can looks like a baked turkey. I started to use humor because this theme represents a heavy issue, that is not going away. We have too many people on the planet, and we're using up our natural resources. Jobs are at stake. We are all pawns in a play that affects us all so directly that it's hard to get the big picture.

It's so hard to make sense of all that goes on in life. Seriousness is like having to control or understand it all. Ultimately, we can't. We have to lighten up. Humor is a way to acknowledge that it's hard and to help us to see things in another light. One woman in the graduate program was appalled by "Wild & Tasty" because she thought the humor trivialized the whole issue. I thought it was interesting to get that kind of reaction, but I was glad to get a reaction. I like using humor. In representational pieces, cartoon-type images work well with textiles. If I wanted something really realistic, I think I'd go to painting.

Next I did a portrait of the spotted owl called "Trespasser" and then a portrait of the chain saw. The three quilts formed a triptych. They were all the same size, with the same format. In "Trespasser," each feather in the spotted owl has a different pattern. It's like a feather robe. Is the logger the trespasser or is the spotted owl the trespasser? Why should this even be an issue? Whose woods are these really? This poses the question that we have to figure out.

Along with these three pieces I had a box mounted on the wall. You could buy mementos of the show--buttons containing part of the chain saw or owl (made from black-and-white photos of the paintings printed on colored paper). I also made T-shirts and scapulars.*

I grew up in an Italian community in Fairfax and I was fascinated by the religious trappings of the Catholic Church. In my middle-class, Protestant home, nobody went to church, but we had a sense of goodness because we were a nice, average family. My dad said he didn't like Catholics, so of course I thought they were interesting. My friends and I used to go to the Catholic Church down the street after school, wrap sweaters around our heads, to light a candle and look at the confessional. It was so European.

I rubber-stamped a spotted owl on one side of my scapulars, and I used red and black threads (for Stendahl, whose book The Red and the Black, about the Catholic Church, I read as a teen-ager). On the other side, I put a chain saw bar. If you bought a scapular and wore it, you too could carry the burden of the spotted owl and the chain saw. I sold these, and gave half of the money to the Environmental Center in Willits and the other half to the Roots of Motive Power at the Mendocino County Museum. This is a group of local loggers, whom I call eco-loggers because they are into sustainable cutting; they are not with the big companies. As volunteers, Roots of Motive Power show how logging used to be. They get the old logging equipment, repair it and periodically have it running at the County Museum.

I did the "Unknown Portraits" series and a fun series called "Endorphins" right after graduate school. These types of drawings bring revelations. Art is a self-searching medium. I always hope to find new aspects of the world through what I am doing with myself. I use dreams and a big mix of images. I think of these as my allies--little creatures I can learn from--friendly beings inside me and everywhere. Endorphins are chemicals released from the brain while you are experiencing pleasure. These portraits are fun and sensuous: insect-like, monster-like, cartoon-like, fun people-beings. They are more of an emotional statement than a meaningful one.

My recent work focuses on life in Mendocino County. There is a landscape of the Sanhedrin mountain range, and an eyeball series. Eyes come from around the mountain and look at all the people, not in an ominous way but as sort of watchers. My kids say it is wonderful to live in a small town as long as you are doing everything right. If you are doing something wrong, everyone knows about it and that can be really oppressive.

There is also a quilt with an image of me scanning the newspaper with a police log and another called "California Summers," which shows California on fire. Every summer California burns. There is a row of houses, foothills and then the mountains, which are on fire. Three-quarters of the quilt is flames. Another quilt called "Moving to the Country, It's a Tick Sky," has a salmon-colored sky with a pattern of ticks. We have to worry about ticks and Lyme disease here. In the lower portion, the trees have been cut down. There is a double-bladed ax in one of the tree stumps. What's really going on? Some trees have been cut down and some are standing. Ticks are part of the beauty and the horror of moving to the country. I am not done with the series, but have no idea what is coming next.

I have enjoyed sticking with quilting as a medium. I'm getting more recognition than I ever dreamed of having. People want to see what I will do next. Some of my contemporaries in the quilt world say, "Your work has changed so much, Linda. What does this mean? You used to do this and now your work is different. Who are you?" I say, "If I showed you my slide show which could take an hour and a half, you would understand." I'm always changing and my art changes. I want to make art and not worry about selling it. If I sell things it's wonderful. If I don't, the work is easy to store because I can just roll it up.

Now I'm trying to show more in regular art galleries with other artists. I like not being so media-specific. I was in a show with three other women at the Grace Hudson museum through September, and my husband Bob Comings and I are showing at the Stewart Kummer Gallery above Gualala and Anchor Bay from August through January. This gallery, owned by Don Endemann, is open to the public for four weekends and then by appointment.

* A scapular is made from two small rectangles of fabric, each with a picture of a saint. Two connecting threads allow you to put them over your head so one fabric is in front and one in back. A rough piece on the backs of each peice rubs against the skin to simulate the suffering of Jesus Christ. You wear scapulars under your clothes so nobody sees them. People wear these even today.

Grace

Millennium Archives

Sojourn

Archives

All Rights Reserved Copyright © 1998 Sojourn Magazine