A Bridge Over the Ocean

by Susan Sher

Parenting has given me immeasurable opportunities for lessons

about love, forgiveness, and honesty. For me, one of the wonderful

by-products of being a mother is the timeless and universal

bond I feel with other parents whose hearts have also been

stretched. When I began the adoption process three years ago,

I could not have imagined my good fortune at being able to

share this parenting connection so vividly with the birth

mother of my daughter.

Prior to adopting my daughter, Hattie, I received paperwork

which provided some limited information about the baby then

known as Tran Thi Lu and the circumstances which led the birth

mom to choose adoption. I learned that Hattie’s birth

mother, Tu, who resided in a farming village just outside

Hanoi, Vietnam was unable to raise her child due to poverty,

a five-year old son to care for, and her own physical disabilities

arising from an amputated leg. I was also informed that at

the time Tu consented to have her two-month old baby girl

placed for foreign adoption, the child had just undergone

surgery for what was described as peritonitis. For a short

time, I hesitated to accept the referral, concerned that the

child may have lasting health problems. I did some serious

soul-searching and stared for days at the photo I had received

of Tran Thi Lu. Like most international adoptive parents,

I took a leap of faith and decided that there was a reason

why this child was referred to me. I knew I was meant to raise

and cherish her for a lifetime.

In September 1998, two days after 11 month old Hattie was

placed in my arms, I attended the Giving and Receiving Ceremony

in Hanoi. I had understood that a family member or possibly

a resident of the village where Hattie was born might appear

at the ceremony to “give” this child to me and witness

the official adoption process. I welcomed the opportunity

to meet a family representative who could provide even a grain

of background information that I could later share with Hattie,

but thought that such an appearance was unlikely. Shortly

after we were seated in the government office where the ceremony

was to take place, much to my amazement, a strikingly beautiful

woman on crutches with an amputated leg, accompanied by a

little boy, entered the room. I knew instantly that she was

Hattie’s birth mom. I walked over to Tu and placed Hattie

in her arms.

Because the officials were busy arranging paperwork, Tu and

I had some time to sit together. She was obviously very happy

to see Hattie and played and cooed with her, while at least

on the surface, Hattie did not seem to know Tu. Although Tu

and I were both shy and unable to speak each other’s

languages, we shared some limited communication. We laughed

when her little son picked Hattie up with some difficulty,

and Tu said something that I knew was along the lines of,

“don’t drop her.” While we sat together, I

found myself sneaking glances at her, trying to memorize her

physical features, her mannerisms, anything that would help

me to know Hattie. I noted that Hattie had inherited her exquisitely

long fingers and beautiful, full lips.

With the help of some quick translation by one of the adoption

agency officials, I was able to find out what I had hoped—that

yes, she would like to keep in touch via updates and photos

and if we were able to return to Vietnam, wanted to see the

child again. I learned that she had seen Hattie two months

earlier in the orphanage, but due to the long trip from her

home and her limited finances, that was the only visit during

the prior eight months.

I regretted that I did not have a gift for Tu—something

that I could give her to express my gratitude for bringing

this beautiful child into my life and in recognition of the

overwhelming loss which I could only imagine she was experiencing.

Aware of her poverty, I decided that money was surely something

she could use. I quickly grabbed a bunch of American bills

from my fanny pack and shoved them into her hand. She nodded

in appreciation and put the bills into her pocket. I started

to cry and we gave each other a quick, awkward hug. I then

moved away so that Tu and her son could have some time alone

with Hattie.

After the very short ceremony and the signing of the paperwork,

we all went outside into the stifling heat of midday. Before

I stepped into the air-conditioned van that awaited us, I

put Hattie in Tu’s arms for one last time. Tu kissed

the baby and quickly handed her back to me. I sat by the window

in the van with Hattie on my lap. As we pulled away, I waved

goodbye to Tu with Hattie’s hand and Tu waved back. It

was one of the most poignant moments I have ever experienced.

That night Hattie cried inconsolably for hours. I could not

tell if it was because of her bronchial infection, tiredness

or—despite how easily she seemed to have parted from

her birth mother—a deeply rooted and subconscious grief.

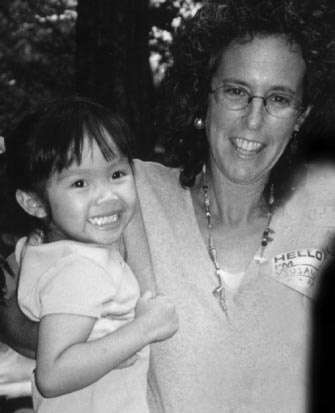

Over two years have passed since that Giving and Receiving

Ceremony. Hattie has grown into a smart, beautiful and healthy

three-year-old. In the Vietnamese tradition, during the past

few years, I have sent a small amount of money to Tu for Tet,

the Vietnamese New Year, along with letters and photos. Tu

very quickly responded to both letters through a friend, as

it appears that she herself is unable to read and write in

Vietnamese. A Vietnamese friend of mine in the town where

I live graciously and patiently translated the letters on

both ends for me and advised me of appropriate phrasing and

etiquette.

Through this brief correspondence, I feel like Tu and I have

in small, but significant ways, shared information about ourselves

and of course, about Hattie (or Lu as we both refer to her)

and as a result, have become some thing like pen pals. The

amount of money I sent was, for me, a small donation, but

for Tu, has meant a great deal. I initially feared that our

link may depend on the gifts of money but it seems that the

connection runs more deeply. Thinking that it would sadden

her to see pictures of Hattie and me together, I carefully

chose to send only photos of Hattie. Tu, however, specifically

asked me to send pictures of the two of us.

Hattie has now lived with me for a much longer time than she

did with Tu and clearly, my friends, family and I, and the

culture within which we live, have indelibly molded her. But

it is Tu’s blood, lineage, and spirit which will forever

be a part of Hattie, who will also always be Tran Thi Lu.

Tu and I each hunger for information about the other world

in which this child has lived—I want to know where Hattie

came from and Tu wants to know who she is becoming. As Hattie

grows more to physically resemble her birth mom, my curiosity

has increased; with the approval of my Vietnamese translator

friend, my questions for Tu have become more personal.

She has responded directly and with no apparent embarrassment.

She explained that her life is very difficult. At the age

of twenty, she was diagnosed with bone cancer and apparently,

with no options for treatment, was told that she would die

if she did not have her leg amputated. Since then, for the

past fifteen years, she has earned a meager living selling

cooking rice paper in the market. She supports her son and

also cares for her ill mother. She has no husband and no other

family who live locally.

Imagining the difficulty of her day-to-day existence, I am

jolted to an examination of my relatively privileged life.

I, too, am a single parent and often feel exhausted and stretched

to the limit. My daily challenges, however, clearly exist

in a different universe. In learning Tu’s story, I see

how it is one of the sad ironies of adoption that the precious

beings whom we can not imagine living without, came to us

as a result of the suffering and loss of others who also loved

them dearly.

In a portion of one of her letters, as it was translated to

me, Tu wrote, “I feel like there is a bridge over the

ocean. Now we are connected as friends.” Those beautiful

words filled me with gratitude for the opportunity to create

a bridge for my daughter between her two worlds and to lessen

the burden of her inevitable search for origins. In recent

months, Hattie has started a practice of standing in front

of our house and waving at the drivers of passing cars. Most

days, she does not want to get into our car until at least

one driver waves back to her. In my quest for symbolic meaning,

I have often wondered if she has already started her search.