|

|

|

|

|

|

This

piece was presented at the panel, "Mother Africa and the Black Madonna,"

as part of the From the Realm of the Ancestors: Language of the Goddess

conference at Cowell Theater, Fort Mason, San Francisco on June 13, 1998,

sponsored by the Women's Spirituality Program, California Institute of

Integral Studies.

My name is Nzinga and I am the great-granddaughter of Ethel, granddaughter of Ethel May, daughter of Erline Olivia. I am the mother of Anthony Leroy, of Rhonda Lorene, of Damon Lamar, and of Derik Lonell. I have two wonderful grandsons, Anthony Isaiah and Justice  Alexander. One came to me last Sunday.

Alexander. One came to me last Sunday.

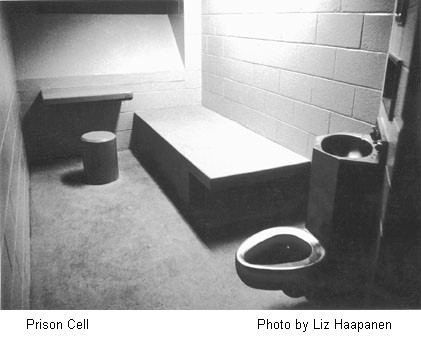

I call on my tribe in a way that centers me and puts me in perfect alignment. I call them to be with me. I invite my ancestors to be present and to bless me with a bit of truth, passed on through cellular memory and intuition, to receive their prayer. I ask for Spirit to bless me and you this morning. I ask that our spirits come close to one another, that we welcome this time as sacred in order to challenge old paradigms and to create new ones based on love, trust and admiration. I recognize myself as a daughter of the tribe--no more, no less--and my work is steeped in copious amounts of spiritual resolve. I do many things with the African-American community having to do with standing up and being seen. There is a special service that I undertake, an honor that I share. That honor is in serving the women who are captured by the United States criminal justice system. I pause now for a moment of silence on behalf of all the sisters who cannot join us this morning. Thank you. There are many daughters missing from our tribe; many mothers who have gone away and will not return soon. There are many aunties and godmothers, nanas and second mothers that are sequestered away in the halls and confines of the "just us" system in America. I've had the privilege of working in many "just us" systems, and I love the work I do. I love the fact that I am able to pass through gates that swish silently closed or clang noisily behind me with authority, letting me know that I will not proceed until someone gives me permission. I love the fact that I can make it there, that I can steel myself against the insults and the injustice and the humiliations of the intake room, through which I have to pass to meet my sisters. I think that the most significant way I am able to bring Spirit forth in my work is when I pass through the gates of entry at the federal prison in Dublin. When I pass through scrutiny and allow myself to be touched, searched and patted down, I protect myself from the looks of "What are you doing here?" I willingly place my bags on the counter and empty my pockets and lift my hands to the air, and they search all that I bring with scrutiny. But because they do not find the love that I have tucked away inside, I pass through. I pass through, pretending to defer to whoever has the keys, to that visible authority. For in Dublin I am called upon to facilitate ethnic specific work to African-American women. I believe in miracles, and I know that it is a miracle that brings me there each week, that allows me to work with sisters--African-American women. And let me tell you this: I work with women from all ethnicities, and I recognize all as children of Creation. I also know that my people are dying, and that it takes special work so that we may survive. It is that special work--graced in spirit, lined with love, created with hope and prayer and a will to get over, to pass through, to stand up, to be seen--that allows me to go every week. When I pass through the gates and I steel myself against the disregard with which I am treated, it is of no consequence to me because I know my sisters are waiting. When I pass through one steel door and then another, and am finally escorted to the room in which they wait, my heart beats fast. I have to hide my happiness. I have to keep my joy way down deep in my heart so no one will know, lest they stop me from coming. As I steady myself and walk across what at first appears to be a campus, my senses reel when I am confronted with so many daughters, so many mothers, some who don't speak English, from all parts of the globe. It's sad to see that they are so used to looking down; they won't look up. I bend down to catch a gaze as I walk by, to share hope and to pass a smile. It doesn't matter if we don't speak the same language. I understand that a heartfelt smile can pass the barrier of the spoken rule. And so I walk in with a sense of humility and joy. When I reach the space that is set aside for us to work, we rejoice, we close the door, we give each other a hug (which is completely forbidden) and we have our sacred sister time. That's the time I bring in folklore about the African goddesses and stories about Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman. That's the time we talk about the advent of chattel slavery and its effect on our lives today. That's the time that Spirit leaps forth in an amazing way and brings us close, close, closer, until we are one. Sometimes I get an unfortunate summons when I'm there. Sometimes my sisters tell me, "Nzinga, you know, um, Mary B. is in the hole. She's in the Shoe this week. She needs you to come and see her." "The Shoe, sister?" I say. "Yeah, you know. She got in some trouble. She's waiting for you down there." So I take a deep breath and I ask for the guards to escort me into the Shoe, into the place of solitary confinement. I tell the sisters that I will see them next week, that I have to go now because I don't have much time there. So we end our circle with prayer while we wait for the guard to come. We hold each others' hands, and I pray for their strength and courage and the ability to withstand another week. I am talking about non-violent, first-time offending women. Many of those women are doing twenty to twenty-five years. Some of them have what is called "double natural life" sentences. Let me just tell you that most prisons in America that house females have about 46 to 52 percent African-American women. In San Francisco we make up 7 percent of the county. There is a mandatory sentencing guideline that says that if you are guilty of trafficking or using crack cocaine, your sentence is 500 times more severe than if it's powder. You might wonder how a law such as this is on the books, but we know who uses crack cocaine and who uses powder. This reality weighs heavily on my soul, and when the guard comes and takes me to the Shoe, I have to pray while I walk behind him. I call on my ancestors to bless me, and I ask for more power and more strength. I ask for more knowledge and more humility so that I might serve in a more meaningful way. The guard takes me through one steel door, another steel door and then another--deep, deep, deeper into the belly of the beast. When at last I'm in the confines of the Shoe, I find my sister in a small room, about the size of a graduated closet. I can't see her until I bend down, until I adopt a position of prayer and try to make eye contact with her through the slit through which they pass her food. "Daughter," I call to her through the slit. "Come here, Daughter. It's Nzinga."  She bends down, her eyes meet mine and we are locked in an embrace at that

moment, which extends over time and space. It passes the authority of the

guards who wait right behind me. It passes the authority of all the steel

and all the concrete that separates us. It passes the authority of the

warden and the sentencing judge.

She bends down, her eyes meet mine and we are locked in an embrace at that

moment, which extends over time and space. It passes the authority of the

guards who wait right behind me. It passes the authority of all the steel

and all the concrete that separates us. It passes the authority of the

warden and the sentencing judge.

Our union is Spirit. And when I look into her eyes, I realize that I'm a time traveler. I don't know whether I am in this time or the time that was before. Which bars are these that she's shaking? Are these the bars that were here during chattel slavery, or are these the bars that are here today--and does it really matter? My message is the same today as it would have been then: "Daughter, wait. Call on Spirit this morning. Call on that timeless space that was passed down from your mother, and your grandmother and her mother's mother before her. "Go into the deep place that is yours. Speak to your own Spirit. Gather your strength. Do not give way to the temptations of anger. Do not waste the breath that Spirit gave you this morning by profane thoughts and profane sounds. Be glad that you've lived another day so that you can be stronger. "And remember," I whisper, "you are sooooo beautiful. Your dark, African skin is amazing." Lovely African eyes fill with water this morning. "It's okay, Daughter, because I am loving you this morning. I am here because Spirit allowed me to pass through to be with you,so that we could hold one another, and each leave each other's presence stronger than when we came together, in a way that's old and magic, in a way that's ours. "So remember, Daughter," as I hear the keys begin to move behind me, knowing that my time is almost up, "you are an amazing descendant of daughters of the African diaspora, and we have survived much, and you will survive this. Remember that your spirit is not for sale this morning. It's not available to the highest bidder; it's yours for now and for eternity. Call on it, sister. Be strong and survive in the fact that I'm loving you, and Spirit stands with us. Aché." "Aché," she says in return.  As I stand up, my body creaking and my knees making noise, I feel like

my job is done as the guard takes me back through one steel door and then

another and another. I finally make it back to the central intake room,

and gather my belongings and leave. By the time I get to my car, I'm crying.

As I stand up, my body creaking and my knees making noise, I feel like

my job is done as the guard takes me back through one steel door and then

another and another. I finally make it back to the central intake room,

and gather my belongings and leave. By the time I get to my car, I'm crying.

"Sweet Jesus," I say. "How long, how long? How long before we realize, as a nation, the travesty and the injustice that affects us? How long before we realize that what affects us affects everybody? How long before we really embrace the fact that all of us, all of us are sisters and brothers in Creation, and that we must help one another lest we all perish? How long, Jesus?" As I sit here this morning I listen to stories of the Dark Mother. I try to record them so that I can take them back. I gather them as precious stones to give an offering for the next time we meet. There is much that I can say about my work, but I will say this: My work is about survival, about Spirit. My work is about sisterhood and love, grace, forgiveness, compassion, adoration and humility. With those ingredients I am able to continue.  As I put my key in the ignition, I wipe my tears, but they won't stop.

I thank Spirit for letting me make it that night, because I saw a tender

seed of hope in her eyes when she pulled back from me in the Shoe. I felt

a resurgence of strength in the hands that I held in the sister circle.

So I know it was a job well done, but it wasn't just my work, you understand.

This is how we use Spirit to do some nation-building. This is how we bring

faith to the forefront, to make Spirit useful for me and for my sisters.

As I put my key in the ignition, I wipe my tears, but they won't stop.

I thank Spirit for letting me make it that night, because I saw a tender

seed of hope in her eyes when she pulled back from me in the Shoe. I felt

a resurgence of strength in the hands that I held in the sister circle.

So I know it was a job well done, but it wasn't just my work, you understand.

This is how we use Spirit to do some nation-building. This is how we bring

faith to the forefront, to make Spirit useful for me and for my sisters.

When I asked them last night, "What do you want me to say in the morning? What is your message?" They said, "Nzinga, tell them that we're not bad women. Tell them we may have made a mistake or two, but we're not bad women. Tell them that we love our children. Tell them that it's so hard to love and raise our children from inside the confines of the ‘just us' system. Tell them we don't deserve this, and we want to go home. Ask them to think about us. Ask them to hold a space." I beseech you in closing: Don't forget the women--the young women and the not-so-young women. Women of all hues and colors. The ones that have missing teeth. The ones that have thinning hair. The ones that have emaciated bodies, driven by the drug of their choice. The ones that have survived one trauma after another only to find themselves housed in the criminal "just us" system. Don't forget them. Do what you can, where you can, when you can, to hold a space for them, make a way for them. They need a segue into your hearts, into your dreams, into your spaces. They need a segue into our institutions of higher learning. They need a place at the table, and most of all they need love, unconditional, everlasting. Unconditional. Un-con-di-tional love is what they're lacking. So I challenge you: Find a way to make a way. I thank you. Nzinga Nantambu focuses on issues of health, healing, love and empowerment

necessary for the survival of the African American community. She

is an instructor at New College in San Francisco and JFK University in

Orinda. Her classes include topics of diversity, incarceration, social

justice and gender. As a consultant for the Federal Bureau of Prisons,

Nzinga has created, facilitated and taught specific clinical incentives

for African-American incarcerated women.

|

| Anna

Marie Stenberg ~ The Core of Being ~ Cover Artist:

Beva Farmer From the Editors ~ Forest Activists: Personal Stories (Introduction) In Those Days ~ Julia Butterfly ~ Spirit for Survival The Way of the Basket ~ Zia Cattalini |

Copyright © 1999 Sojourn Magazine.(All Rights Reserved) |